Before Jerry Dipoto went and did that thing he does—in this case, dealing for Dee Gordon—the big news of the Thursday hot stove was Tyler Chatwood’s three-year, $38 million deal with the Cubs. Many were quick to point out Chatwood’s velocity, groundball rate, and relative youth as the primary factors in his big payday, and the hard-throwing righty turned an intriguing profile into several years of financial security from one of MLB’s top teams. For Chatwood, the deal was likely a no-brainer, and, considering his final contract size, he likely had several similarly lucrative offers on the table.

The Cubs are likely very pleased with this deal as well, making the only noteworthy signing prior to the watershed that will be Shohei Ohtani’s eventual deal (Mike Minor, living up to his name, is not noteworthy). The reigning NL Central champions struck early on the free agent market and filled one of the two rotation spots vacated by Jake Arrieta and John Lackey, and they did so with room to add more pitching at similar or higher cost. At 27, Chatwood was the youngest starter on the market, and he complements a cadre of Cubs starters born in 1989: Chatwood is nine days younger than Kyle Hendricks, and not quite one year younger than José Quintana. The righty is not an over-the-hump stopgap as much as a long-term cog, or at least that is the Cubs’ hope.

I want to add to the few pieces that others have published about the quality of Chatwood’s pitches. Eno Sarris profiled Chatwood’s high-velocity, high-spin repertoire, headlined by Chatwood’s four-seamer and curveball. I’m not a believer in spin rate as a useful measurement, but I do think that Sarris’s suggestions about arm slot and movement are salient. The righty has an opportunity to show off three or four above-average pitches (his four-seamer, sinker, slider, and curve), and his changeup could be a serviceable part of his mix. How? Well [pushes up glasses on nose], it’s science.

Chatwood has one of the steepest curveballs among starters, with lots of drop and relatively small horizontal movement, and this could be an exceptional quality that Chatwood can use to his advantage. Like his new teammate Mike Montgomery, he uses his 12-6 curve to induce groundballs, a somewhat unorthodox approach. In 2017, opponents hit a paltry .091 versus the pitch, and slugged only .164. He even got a nearly-40 percent whiff/swing rate. Unlike most other pitches, Chatwood showed little favoritism when deploying his curveball in sequence with other pitches: he preceded it or followed it fairly equally with four-seamers, sinkers, and sliders, and other curveballs. It’s clearly a good pitch that should be used a lot, but Chatwood tossed it only 11 percent of the time in 2017—slightly more often to lefties than righties.

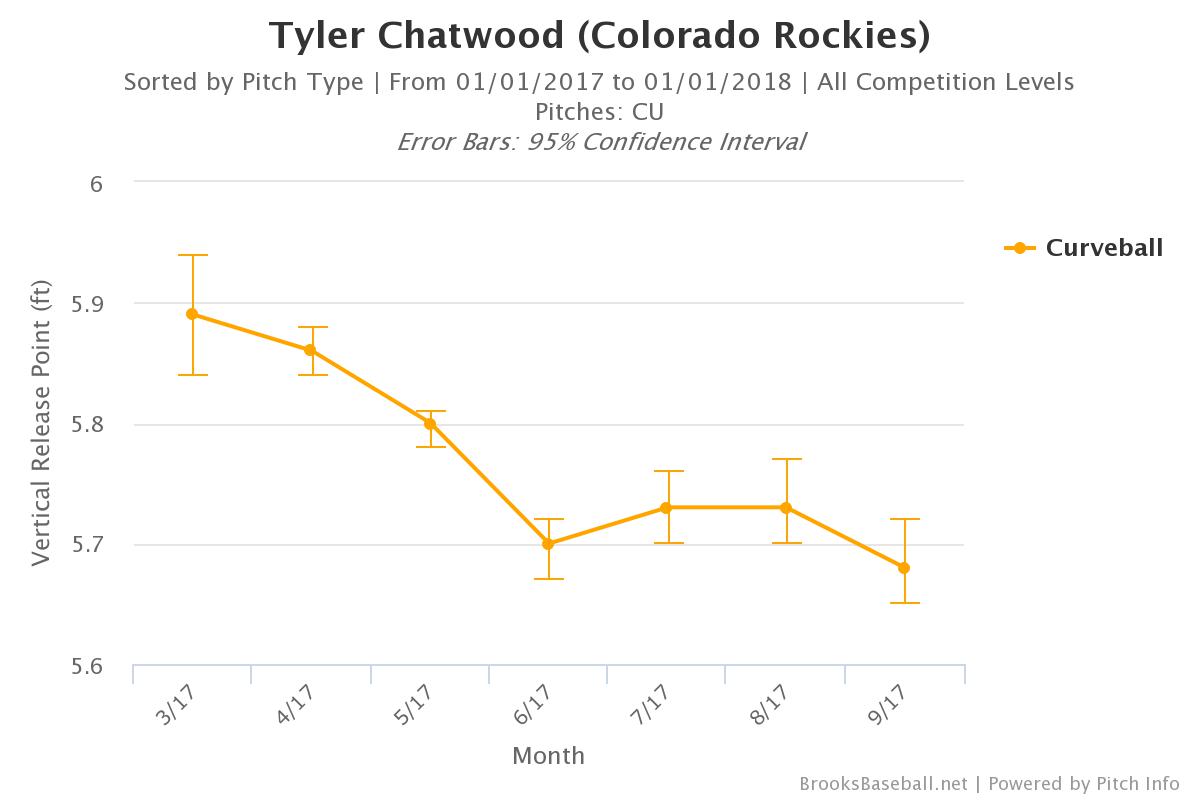

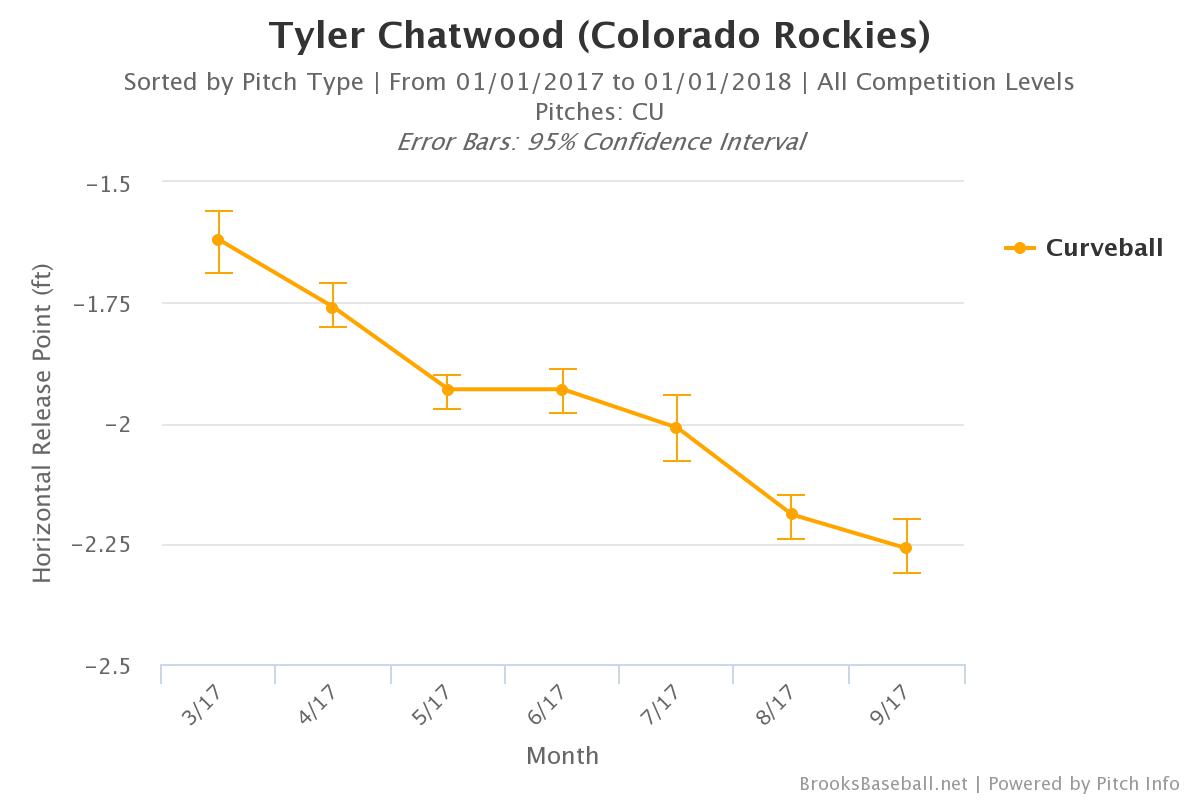

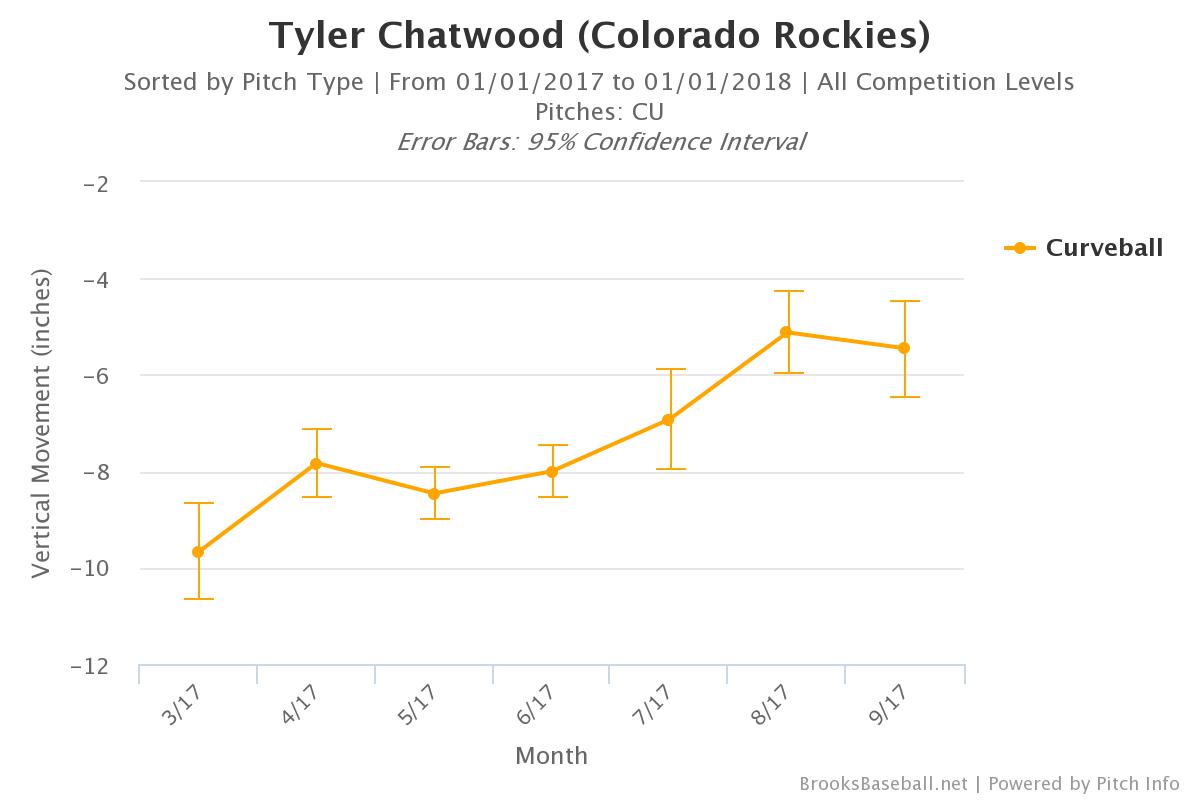

As 2017 wore on, Chatwood dropped his arm slot to a more three-quarters location. For a curveball that should feature vertical movement and minimize horizontal movement, this had an adverse effect. Look at Chatwood’s arm slot and vertical movement on the pitch as the season developed:

This is not necessarily the trend one would like to see from Chatwood. However, there is a mitigating factor: the thin air of Colorado eats breaking balls alive, neutralizing movement that would otherwise be effective. Ergo, Chatwood’s dominant curve faltered at Coors Field, flattening out and losing its exceptional quality. In Sarris’s piece, he split Chatwood’s movement measurements so we could observe Chatwood’s much sexier curve away from home. Away from Coors, his pitches drop significantly more, as they meet more air resistance on the way to home. The result is, as Sarris notes, three more inches of vertical movement on his curve, diving toward the dirt. With the heavier air in Chicago, he could turn his curve into a hammer.

There are warts on Chatwood, too, of course. Cameron Goeldner, who has covered Chatwood for a few years, indicated that his home/road splits have grown since his second Tommy John surgery in 2014. Goeldner also reiterated Chatwood’s volatility. Even if the pitcher were to throw his optimal curve all year, he could continue his trend of alternating brilliant outings and clunkers. There’s a reason for that. On Twitter, BP’s Harry Pavlidis opined that there could be a Jake Arrieta-in-Baltimore-like problem with Chatwood’s fastball command. A dynamite curve won’t matter much if Chatwood can’t locate his fastball. And, despite his democratic usage of his curveballs, Chatwood’s pitch sequencing stands out. In 2017, his top three pitch pairs were all consecutive uses of the same pitches: four-seam/four-seam, sinker-sinker, and slider-slider. This could be a failure in game planning, or it could be the result of a loss of confidence in his fastballs.

A few final thoughts: new Cubs pitching coach Jim Hickey has a reputation of helping improve pitchers’ changeups. This could prove an interesting wrinkle, as it might have unexpected influence on Chatwood’s pitch mix and sequencing. Also, the Cubs might see a mechanical change that could accentuate his fastball or curveball effectiveness, as they did with Arrieta. Chatwood has the stuff; the Cubs will want to help him harness it. With a new home ballpark and an organization that has had some success altering pitchers’ mechanics and usage, Chatwood might find new pathways to success.

Lead photo courtesy Ron Chenoy—USA Today Sports