If you’ve watched a lot of Kyle Hendricks this year (and let’s be honest – if you’re reading this, you have), and if you’ve thought he seems a little off, don’t worry; you’re not alone.

Hendricks himself has noticed, as he explained after last Sunday’s loss to the Pirates: “I’m just fighting myself on some of my mechanics…so that’s really where the problem’s at.”

We’ve come to expect a lot of Kyle Hendricks, and it’s telling that despite his having just tossed five innings of one-run ball, despite a team-leading 3.12 DRA, despite getting more called strikes than pretty much anyone else in the world, Hendricks’s focus is on fixing a problem.

The problem in question is Hendricks’s newfound tendency to give up the long ball: 13 over his first 13 starts in 2018, in fact. In last Sunday’s game, the lone earned run Hendricks surrendered came in the form of this Josh Harrison leadoff solo shot.

Hendricks is currently allowing 1.51 home runs per nine innings, the 19th-highest mark among qualified pitchers in MLB. He’s on pace for 32 home runs, which would obliterate his previous season-high mark of 17 and make him just the sixth Cubs pitcher this century to allow 32 in a season. Through 13 starts, he’s already got three multi-homer games on his ledger; prior to this year, he’d had six such games in his entire career. On the surface, it certainly looks ugly.

But how much of a “problem” is this? And if so, where are the homers coming from? Most importantly, is this a trend we can expect to continue to see moving forward, or is the remedy as simple as “get back to work, focus on it every day,” as Hendricks said in his post-game interview?

That’s a lot of questions, so let’s tackle the “problem” question first, because to be honest, it’s the easiest one. Yes, it is a problem when a pitcher, once renowned for his ability to generate weak contact and keep the ball in the park, suddenly can’t keep the ball in the park.

Now, to be clear: it may not be as much of a problem with Hendricks as with other pitchers. He owns a 6.0 percent walk rate, the lowest on the team, which means that many of his homers will be solo shots. Nine of them have been this year, in fact. And although Jon Lester might disagree, Hendricks can survive the occasional solo shot.

Even so, Hendricks’s newfound tendency to allow homers is most definitely an issue, and the issue is compounded when you factor in the various maladies afflicting the rest of the Cubs’ starters: Yu Darvish has been a frustrating mix of ineffective and injured; Tyler Chatwood is in a one-man race to see how quickly he can exceed his PECOTA projection of 61 walks for the year (he’s currently at 58…you’re almost there, Tyler!); Jose Quintana has been erratic, and while he’s turning things around, he looks far from the burgeoning ace it appeared he might become after moving to the NL; and Jon Lester, though the results have been there so far, seems doomed for regression, as he currently has the largest gap between FIP and ERA in Major League Baseball. As a unit, the starters have a 4.58 DRA, ranking just ahead of the Oakland’s mishmash of starters including players like Daniel Gossett, Daniel, Mengden, and a pair of Cubs castoffs in Trevor Cahill and Paul Blackburn.

Any way you slice it, this has been far from the third-best rotation in baseball, which MLB.com pegged them as at the start of the year. And while Hendricks has mostly been pulling his weight, the Cubs are clearly in dire need of some stability in their rotation. Much of that may depend on whether or not Hendricks can stop the bleeding and solve his homer problem.

So where are all these home runs coming from?

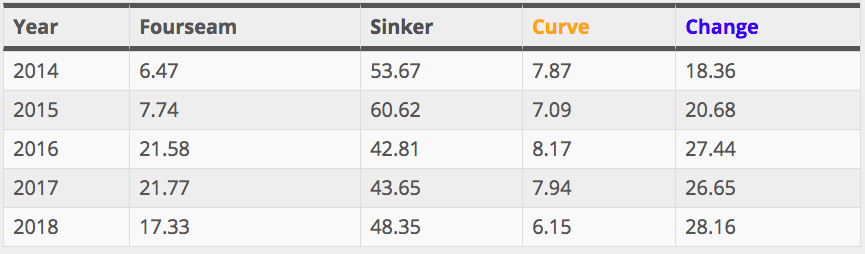

One notable change Hendricks has made this year is an even greater reliance on his sinker, mostly at the expense of his four-seamer. Take a look:

It makes sense: with his velocity topping out at 89, Hendricks long ago shed any illusions of being able to overpower big-league hitters. In the “fly ball revolution,” where pitchers are adapting to hitters’ upward-shifting swing planes by aiming higher in the zone, Hendricks is doubling down on his sinking pitch. Ever since debuting in 2014, Hendricks has felt like an anachronism in the modern game, which is predicated on velocity and punchouts over deception and precision. Lacking the ability to generate whiffs up in the zone, Hendricks is forced to find new ways to adapt.

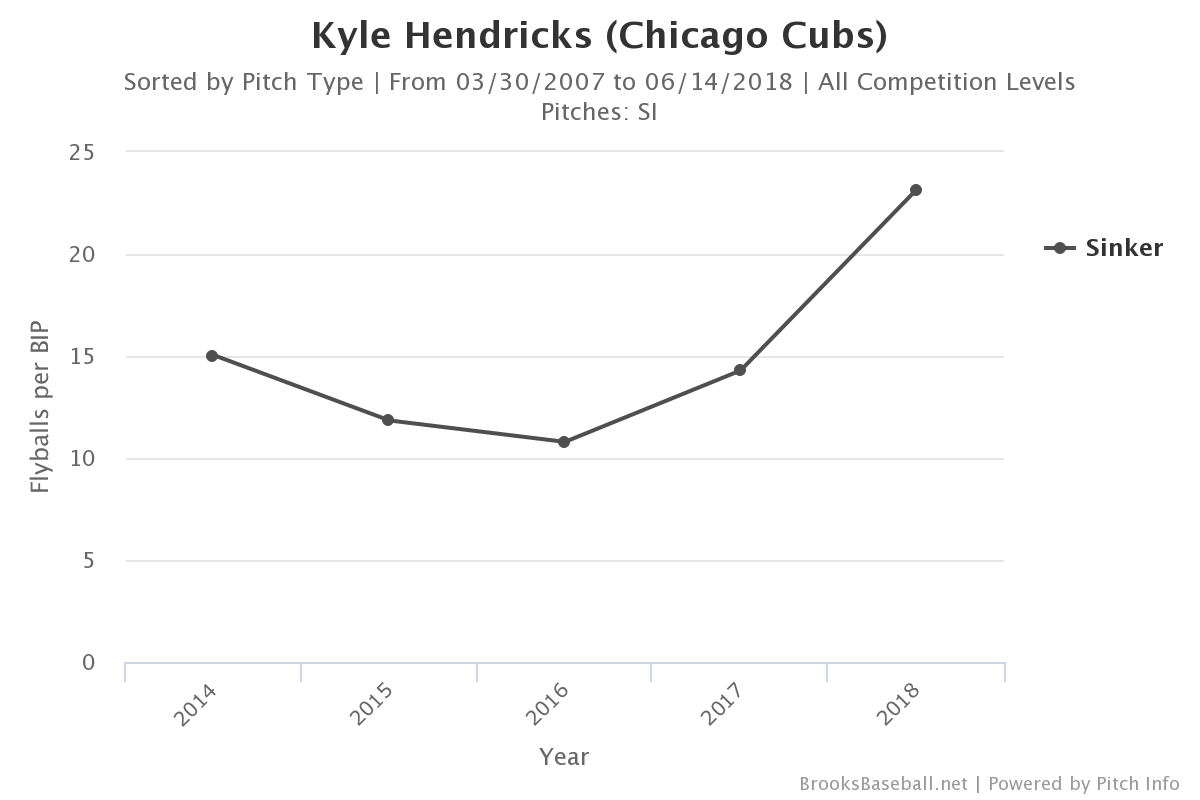

The result of Hendricks’ increased sinker usage has not been more topped grounders, but instead, more fly balls. Over the past few seasons, hitters have been increasingly able to get underneath Hendricks’s sinking pitch. Here’s a chart of fly balls per ball in play on the pitch. Notice the steady dip in fly ball rate during Hendricks’s best years (2015, 2016), and the rapid increase over the past two years, when he’s begun allowing more long balls:

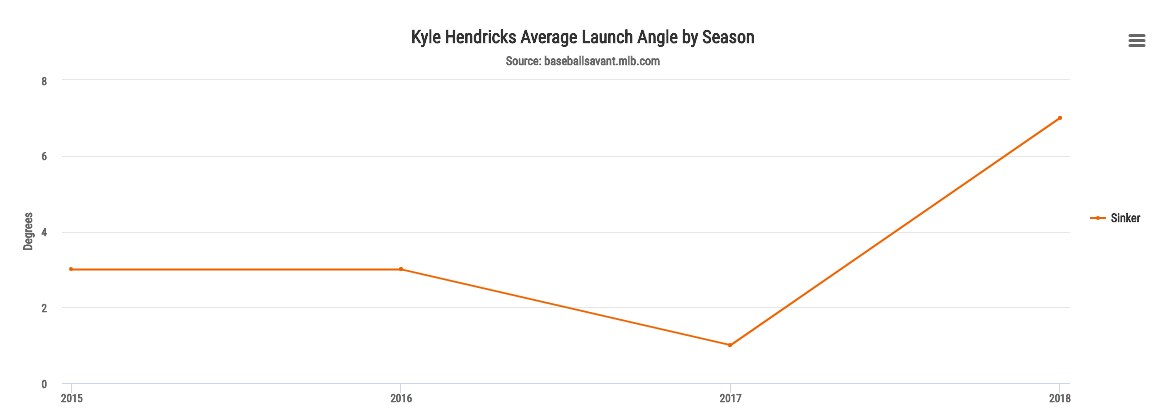

For a bit more evidence, we can turn to the launch angle numbers provided at Baseball Savant, which show the extent to which hitters have been able to elevate Hendricks’s sinker this year:

While none of Hendricks’s offerings have been immune to the long ball, the majority of the damage is occurring on his sinker, with six long balls surrendered on that pitch this season in 558 pitches thrown, or one homer every 93 times he throws the pitch. Just to contextualize a bit: last year, Hendricks allowed a homer once every 140 sinkers thrown; in 2016, he gave up a home run once every 360 sinkers; in 2015, one in every 177. Hendricks is Hendricks, and it’s possible this will all even out. But it appears that he’s failing to command the pitch the way he once did, and hitters are taking advantage.

Now, for the last question: are these home runs going to continue?

For Kyle Hendricks to return to his homer-suppressing ways, the sinker has to be working, and he has to be locating it far down enough in the zone that hitters can’t elevate it. He simply hasn’t been doing that this season, at least not to the extent that he once did. When he is forced to put a pitch upstairs (as he did in the Harrison at-bat above), he’s not getting ANY whiffs up in the zone, and he’s getting crushed in that area.

None of that sounds promising, but there are reasons for optimism. It’s certainly possible that Hendricks is one mechanical tweak away from commanding the sinker the way he once did. And besides that, the home run spike can be at least partially explained away by plain old bad luck. Hendricks is sporting a 17.3 percent HR/FB rate, the 11th-highest in MLB. Prior to this season, his HR/FB rate had been right around league average, at 10.7 percent. And at the same time that he’s allowing a much higher rate of home runs, the average distance on the home runs he’s allowed is right in line with his career marks:

2018: 396 feet

2017: 398 feet

2016: 401 feet

2015: 389 feet

The game of baseball is constantly evolving, and pitchers must continually adapt in order to stay ahead of hitters. It’s difficult to watch the 2018 version of Kyle Hendricks and not see a pitcher who is still tweaking, still making adjustments, still searching for his answer to the launch angle revolution. If anyone can solve this home run problem, though, it’s The Professor.

Lead photo courtesy Jim Young—USA Today Sports