If hitting is contagious, as many are wont to believe, then the Cubs (last night excluded) have a pernicious cold on top of the flu with some sort of weird infection to top it off. After scoring five runs in five games versus the middling Pirates and lowly Tigers, all courtesy of the solo home run, and splitting the Pirates series due only to a pair of great starting pitching performances and characteristically great bullpen work, some resignation has set in among observers of this Cubs team. Maybe they really are built to run hot and cold more than any other contender, or maybe Joe Maddon and Chili Davis’s all-fields/contact approach has had some unforeseen consequences.

While there is a whole slate of culprits causing this dreadful slump, the most concerning must be the normally steady-hitting backstop who has been a cog in the Cubs lineup for three seasons now.

Almost 1200 plate appearances into his career, and Contreras has been a model of all-around offensive consistency. His career slash line is .274/.356/.466, and his stats in each of his three seasons have been remarkably close to those three numbers. His strikeout and walk rates this season are 22.4 percent and 9.8 percent, respectively, right in line with his 22.9 and 9.9 percent rates for his career.

So, everything seems hunky dory for Contreras, right? Well, maybe, except for one glaring exception: this year, Contreras’s power has gone *poof*, with only nine home runs and a .418 slugging percentage in 438 plate appearances. For comparison, in his first two big-league campaigns, Contreras slugged nearly .500 and hit 33 homers in 711 plate appearances. His 2018 ISO is a mediocre .153, 40 points lower than his career mark. Clearly, Contreras has faltered at the plate in some way, and if the Cubs are to regain their intimidating offense, Contreras is going to have to contribute.

So what the hell is wrong with Willson Contreras?

Before I offer a definitive answer for that question—well, as definitive as a baseball writer without intimate knowledge of the Cubs’ hitting philosophy and Contreras’s gameplan can offer—let’s look at Contreras’s batted ball profile, since that’s usually a good place to start. The Venezuelan catcher hits the ball hard, and in both of his first two major-league seasons, he boasted a hard-hit rate better than league average and a soft-hit rate lower than league average. Oddly, he also hit the ball on the ground at a rate much higher than league average: his 54 percent groundball rate was 10 full points above the league average in those two seasons! But the combination worked for Contreras, who used his good speed to post BABIP numbers of .339 in 2016 and .319 in 2017.

Many of Contreras’s grounders found holes, as he hit the ball very hard. His flyball rate, which was between five and seven points lower than league average those two years, didn’t cap his offensive production, since he was launching a full quarter of them (!) over the fence. Contreras had a unique hitter’s profile, and it allowed him to succeed as a solid all-around hitter despite his average walk rate and worse-than-average contact numbers.

This year, things have changed. In what has likely been a conscious decision, Contreras has hit more flyballs and fewer grounders. Two months ago, BP Wrigleyville’s Josh Cole took stock of Contreras’s altered approach, comparing his batted ball rate stats and his average launch angles to produce a pretty stark picture. Here, I’ll do the same (as always, take launch angle data with a grain of salt, as Statcast still has some issues and there isn’t other public data available):

| GB% | FB% | Hard Hit % | HR/FB% | Avg. Launch Angle | |

| 2016 | 54.3 | 27.7 | 32.3 | 23.5 | 5.9 |

| 2017 | 53.3 | 29.3 | 35.5 | 25.9 | 5.9 |

| 2018 | 48.0 | 33.3 | 30.8 | 9.7 | 9.2 |

*Rate stats from FanGraphs, Launch Angle from Baseball Savant.

There’s not really room for another interpretation: Contreras has decided to hit the ball in the air more, and he’s hitting the ball softer overall as a result. This has torpedoed his home run per flyball rate, which is now below league average. As Josh pointed out, his 25 percent rate wasn’t sustainable, but it’s alarming for Contreras’s fortunes to swing so hard in the other direction.

For much of the season, this wasn’t really a problem for Contreras. Through the All-Star break, Contreras was hitting .279/.369/.449, exhibiting a little less power than in previous years but still hitting for a solid average and getting on base at a very good clip. His strikeout rate was down to 20 percent, and his walk rate settled at 10 percent over those 341 plate appearances.

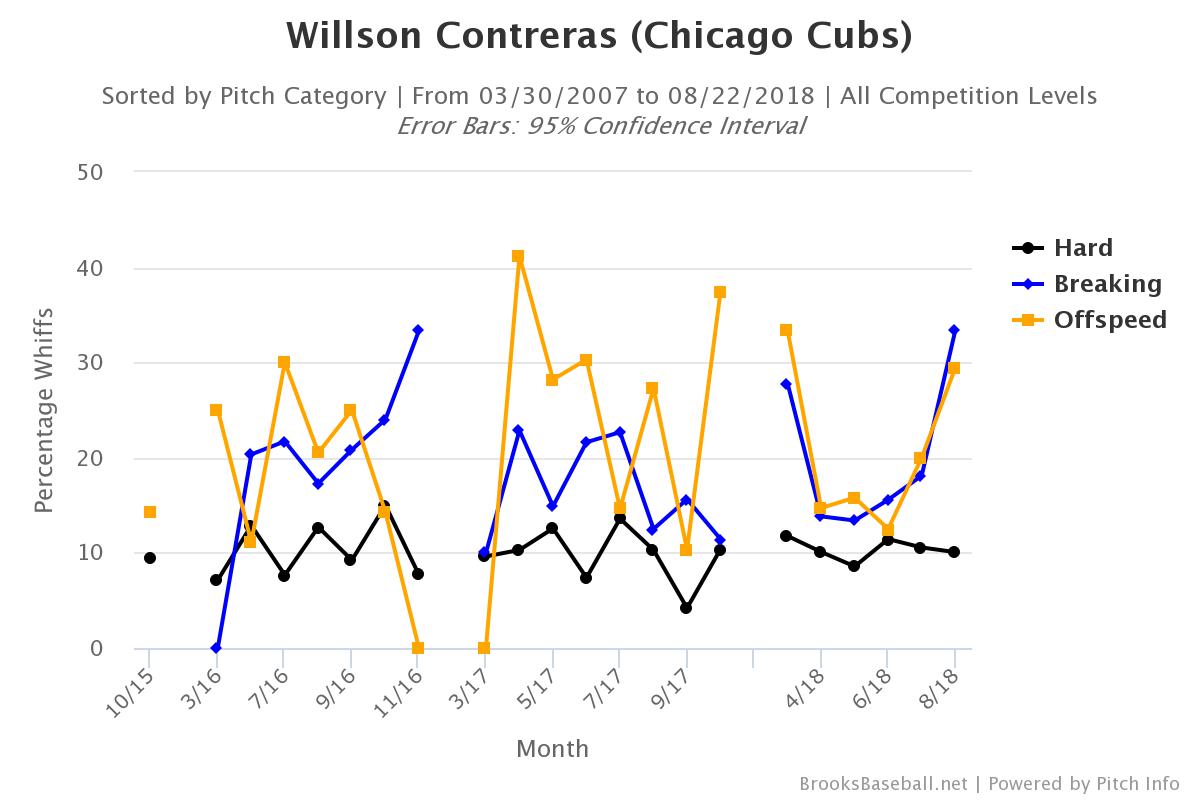

Since the break, though, Contreras has scuffled. That strikeout rate has spiked a bit, up to 27 percent, and he’s hit a thin .221/.309/.314 over 97 plate appearances. The eye tests bears this out—Contreras has looked lost at the plate at times, an unusual occurrence for him. A quick glance at Brooks Baseball’s whiff data proves that our eyes do not deceive us.

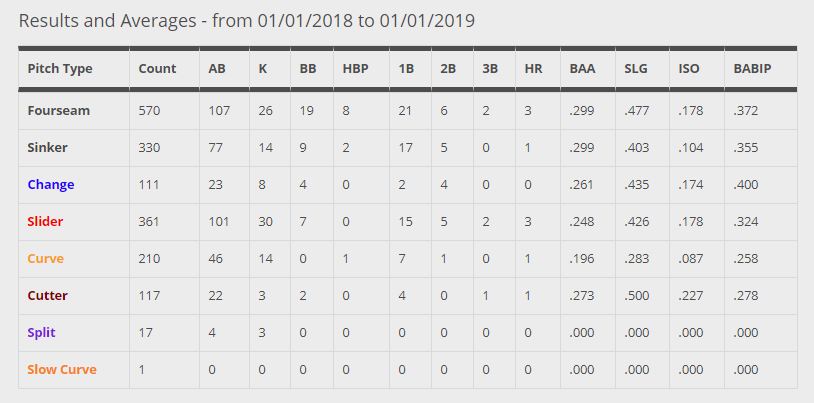

Contreras consistently puts the bat on the ball if a fastball of any variety is coming his way. That’s a good quality to have, and it’s been tough to beat Contreras with velocity at any time in his career. This season, he’s hit .299 against fourseamers, .299 against sinkers, and .273 against cutters, with .477, .403, and .500 slugging percentages, respectively. When Contreras makes contact with a fastball, good things happen.

Over his career, though, Contreras has had varying success making contact with breaking and offspeed pitches. He’s been able to succeed at different times even while whiffing often against those offerings, but it’s easy to see that, in July and August this year, his whiff rates versus those pitches have skyrocketed. So far in the month of August, Contreras has flailed at a full third of the breaking balls he’s seen, and nearly 30 percent of offspeed pitches. While Contreras has been able to stay on the fastball, pitchers have stymied him with a variety of breaking and offspeed pitches, even while they haven’t thrown more of those pitches as a percentage of total offerings. Things could get worse before they get better for Contreras if opposing hurlers get wise to this trend and start throwing fewer fastballs.

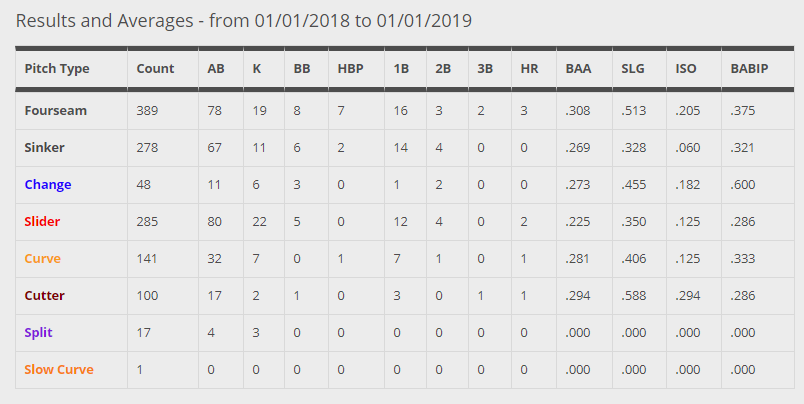

There’s still some unusual data that doesn’t quite fit in this framework, though. Contreras has actually hit sliders and changeups very well this season. Check out his performance against different pitches this season and marvel at Contreras’s consistency:

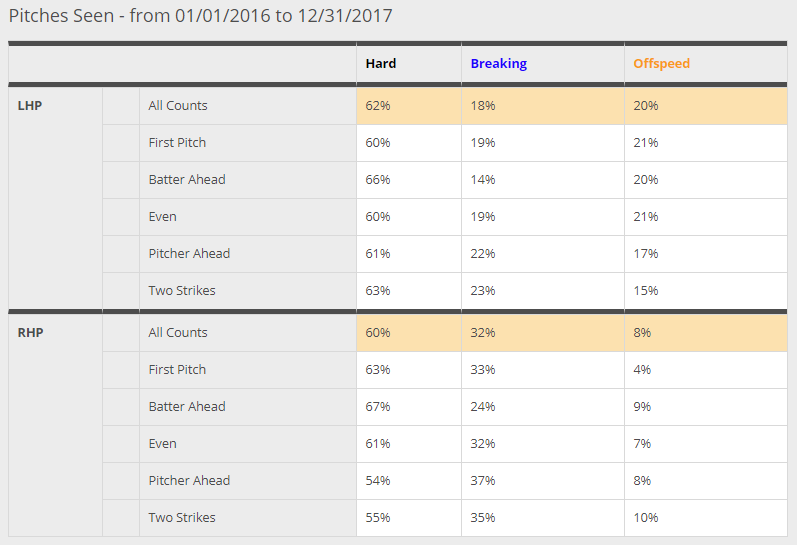

The only pitch he really struggles against is the curveball, but Contreras hits sliders and changeups as well as he does fastballs. This has generally been the case for his whole career, too. I had my doubts that this trend couldn’t also be reconciled, so I decided to slice Contreras’s numbers in one more way. Here are side-by-side comparisons of how pitchers have attacked Contreras in 2018 versus how they did in 2016-2017.

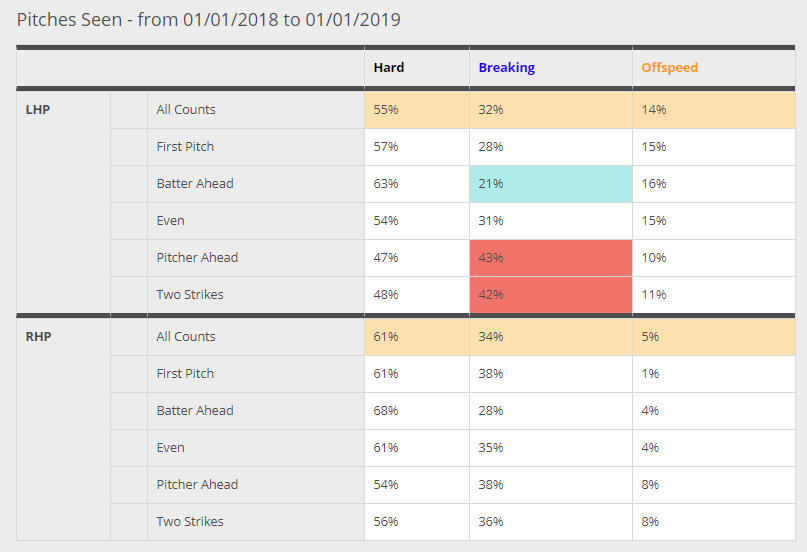

Brooks Baseball has made it very easy to see what has changed. Before this season, opposing pitchers were surprisingly democratic with their deployment of different pitches when facing Contreras, likely a function of his ability to hit almost all pitch types well. This season, left-handed pitchers have taken to throwing a lot of breaking balls to Contreras in two-strike counts, doubling their frequency with the pitcher ahead or with two strikes. They’re also giving him fewer fastballs to hit in all counts.

But Contreras isn’t hitting lefties worse than he has in the past. Rather, he’s hitting righties worse. This season’s .750 OPS versus right-handers is significantly worse than 2017’s .828 mark, or 2016’s .841. So, again to the data well, this time split to see only righties:

Ah, there it is!

This is a lot to look at, but focus on how Contreras has hit righties’ sliders across these two time frames. In his first two seasons, he saw 454 sliders from righties and hit .271 with a .475 slugging percentage. That’s pretty good! And, perhaps unsurprisingly for the preternaturally consistent Contreras, right about where his overall career numbers are. This year, though, those two marks have plummeted to .225 and .350, with a 78-point drop in ISO. Contreras is doing poorly against sliders from righties, and this makes sense considering the ballooning whiff rates we saw for July and August.

So far, right-handed pitchers have not begun to throw Contreras more sliders due to his struggles against them. In fact, since the All-Star break, he’s seen slightly fewer sliders (and total breaking balls) from righties. Those pitchers have started to throw him more sinkers, however, which, as we can see in the last chart, Contreras has struggled to hit with authority this season. This could merely be a function of the specific pitchers Contreras has faced since the break, or it could be the beginnings of an adjustment to which Contreras will have to counter-adjust.

Will he make that adjustment before the season is out? There’s no guarantee that he will, but Contreras has proven himself a good all-around major-league hitter, and he has made adjustments constantly in his nearly ten-year pro career. One thing is for certain, though: the Cubs are going to have a difficult time in September and October if Contreras doesn’t adjust.

Lead photo courtesy Rick Osentoski—USA Today Sports

Excellent breakdown. Thank you.

Plawecki really doesn’t uppercut much. He’s a guy who more chops down on it, which is why we see him hit a lot of grounders.