On Thanksgiving Day in 1887, as the story goes, some 20 members of Chicago’s Farragut Boat Club gathered to celebrate the holiday when a group of them began tossing a boxing glove around the hall. Eventually one of them struck the glove with a broom handle, sending the glove flying into the lap of one George Hancock, who voiced his desire for an impromptu game of baseball indoors. With the glove serving as a ball, the broom handle as a bat, and nine players arranged throughout the hall, the game commenced. After several hours, the event concluded, and George Hancock, inspired by the action yet deeply dissatisfied with its clumsiness, asserted he would create a list of rules that would govern each subsequent game of indoor baseball.

The Rules of Indoor Baseball

Hancock returned to the Farragut Cub the following Saturday with a list in hand, informally establishing the rules that would characterize the game for decades. While many of the rules were directly lifted from professional baseball (the strike zone was from the knees to the shoulders, three outs constituted a half-inning, etc.), others had to be adapted to fit the parameters of indoor spaces. The bases were to be 27 feet apart, the pitcher 23 feet from home plate, and the distance from home plate to second base stood at 37.5 feet. Of course, these dimensions could be adapted to fit the size of the hall in which the game was played.

As for the uniforms, they largely mimicked mimicked professional baseball ones, with matching shorts and knee-length pants, as well as high socks. However, it would not do to have cleats scraping away at the club’s expensive flooring, and so players’ shoes must have rubber soles. Additionally, all players must be fitted with knee and elbow pads.

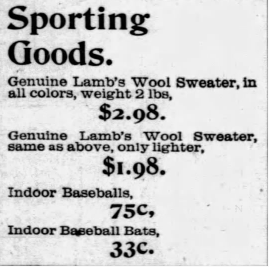

In 1891, four years after inventing the sport, Hancock released the official rulebook of indoor baseball. Of note, the rulebook stipulated that the ball must “be 17 inches in circumference, made of a yielding substance, 8 1/4 ou nces in weight, and covered in a white skin.” (5) Likewise, the bat must be like a broom handle precisely “2 3/4 long….it must be made of wood except that a metal rod….may be passed through the center.” (6) Complementing this unusual equipment were several rules stipulating that pitchers must throw underhand without the use of curveballs. If any pitcher were to break these rules, they would be immediately ejected from the game.1.

nces in weight, and covered in a white skin.” (5) Likewise, the bat must be like a broom handle precisely “2 3/4 long….it must be made of wood except that a metal rod….may be passed through the center.” (6) Complementing this unusual equipment were several rules stipulating that pitchers must throw underhand without the use of curveballs. If any pitcher were to break these rules, they would be immediately ejected from the game.1.

The final and perhaps most whimsical rule change concerned a parenthetical in the section on bases: “[if, in sliding with the bag at any base, he should stop, he must then return with the bag to the proper spot before starting for another base].” In indoor places where it was impossible to fix the bases to the ground, this rule accrued much use.

By the publication of this rulebook, all of the major clubs around Chicago had already adopted Hancock’s ideation of indoor baseball. In the ensuing years, the rulebook was disseminated throughout the country, connecting various small leagues in cities like Philadelphia, New York, and St. Louis with one another via a standardized form of the sport. As the rules became more accessible, participation increased, and the sport became a viable alternative to outdoor baseball.

Growing the Sport

The sport quickly spread to other clubs throughout the city, and by the end of Winter, many of the most prominent men’s clubs had adopted it as routine recreation. The games always drew crowds of both club members and wealthy visitors who were admitted for the spectacles in hopes they would eventually become members. However, as the sport spread to other cities, it eventually evolved into an activity played at just about every public school across the country.

By the early 1890s, multiple leagues had formed throughout the Chicago area. Each team consisted of upper middle-class white men who used the sport as a means of solidifying their position as a racial and economic force within the city. As dues for most of these clubs amounted to $75, or one-eighth of the median Chicago family’s annual earnings of $600.2 First formed was the Northwestern In door Base-Ball League, headlined by Hancock and the Farragut Club. In 1890, the league welcomed a rival, the Chicago League, headlined by the Harvard Club. By 1891, both leagues explicitly banned outsiders in order to ensure both players and attendees were “representative society people.”3

door Base-Ball League, headlined by Hancock and the Farragut Club. In 1890, the league welcomed a rival, the Chicago League, headlined by the Harvard Club. By 1891, both leagues explicitly banned outsiders in order to ensure both players and attendees were “representative society people.”3

In the initial years, the leagues often hosted charity events for organizations like the Illinois Humane Society. Such games gathered crowds of upwards of 3,500 as admittance was extended beyond club members to anyone wealthy enough to pay the admission fee plus larger donations. As a result, the crowds were vastly more socio-economically diverse than was standard. Indoor baseball slowly spread throughout the city, beginning with bankers before being taken up by tradespeople and children. Though the sport became increasingly popular since the inaugural charity game, it was not until its debut as part of the World’s Fair in 1893 that indoor baseball began to truly universalize itself.

In honor of hosting the World Fair’s, Chicago held the first truly accessible public indoor baseball game. The teams, the Lake Forests and the Irvings, played in Irving Hall, a two-story public building on the corner of Paulina and Madison that was best known for holding political rallies and other public events. A temporary grandstand was constructed in order to help accommodate the 500 spectators, the majority of whom were working class people who were able to finally see the sport from the newspapers brought to life.

The intensity with which the crowd rooted for each team would ordinarily have been remarkable, but due to the dictatorial nature of circumstance, reporters came away with a much different tale. In the middle of the game, the temporary grandstands gave out, collapsing on a crowd that included a 15-year-old boy who was hospitalized with a fatal head wound. The remainder of the spectators stampeded out of the hall, leaving behind broken pieces of timber and splatters of blood.4

Nonetheless, the working class was finally allowed into the world of indoor baseball and there they would remain. By the mid-1890s, as indoor lighting grew cheaper and more accessible, indoor baseball became an integral part of defining and unifying ethnic and class-based communities throughout the city. The German-American working class had their own team, as did the Black community, and so on.

Nonetheless, the working class was finally allowed into the world of indoor baseball and there they would remain. By the mid-1890s, as indoor lighting grew cheaper and more accessible, indoor baseball became an integral part of defining and unifying ethnic and class-based communities throughout the city. The German-American working class had their own team, as did the Black community, and so on.

By the end of the 20th century, Chicago’s wealthy gave up their hold on indoor baseball, enabling it to become far more diverse than the outdoor version. Just a decade after Cap Anson instigated a ban of POC in professional baseball, Chicago high schools formed integrated indoor baseball teams. Hosting their games in YMCA spaces, school libraries, church halls, and other public venues, these high school players kept the sport alive when older men turned away from it. They enabled a growing number of people to access the sport, eventually leading to the acceptance of girl and women players.5

AG Spalding and the Final Years

As the country approached WWI, many cities which had formerly embraced indoor baseball abandoned it en masse in favor of basketball. Chicago was the exception. In the early 1890s, A.G. Spalding campaigned hard against indoor baseball, fearing it would damage the reputation of baseball and subsequently bankrupt him.6 However, in the 1910s, when his position within baseball was nearing an end, he created an integrated indoor team which revived interest in indoor baseball throughout Chicago and gave him the incentive to provide indoor baseball equipment at a discount.

Several decades after most cities gave up on the sport, Chicago held one of the final tournaments in 1933. It involved over 1,000 youth from Illinois and the surrounding area and served as a final farewell. In the ensuing years, Chicago finally fully committed to the outdoor version of indoor baseball––softball.

Notes:

1 George Hancock, Indoor Base Ball Guide: Complete Instructions for Playing The Game, With Description of Material Used, (Chicago: Hancock, 1891), 8-13.

2 Historical Statistics of the United States, Table Cd465-473 – Consumption expenditures of families, by income class: 1888-1891.

3 Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1891, pg. 2.

4 Chicago Tribune, November 23, 1893, pg. 1.

5 Patrick Mallory, The Game They All Played: Chicago Baseball, 1876-1906, (Loyola University, 2013), 108-120.

6Pittsburgh Dispatch, January 1, 1891, pg. 6.