It’s a cliché to note that there are no hardasses like Dallas Green in baseball anymore. I would be remiss to ignore it, however: there truly are no baseball executives or managers like Dallas Green anymore. For decades, Green was the irascible firebrand who played for, helmed, and constructed two of the National League’s longest-suffering franchises, leading with clear vision and with no pretenses to making friends along the way.

Green was nearly 50 years old when he took over the Cubs in the wake of the Tribune’s 1981 purchase of the club. The longtime Phillies player and manager was coming off a World Series victory, the Phillies’ first in their long history, but the intractable manager failed to endear himself to the players over which he presided. Some sources impute unto either Larry Bowa or Greg Luzinski—it depends on who you ask—a rather unfortunate epithet bestowed upon Green: “Gestapo.” The Tribune Company coveted the man’s sharp mind, though, and decided that not his penchant for strict clubhouse rules not an obstacle. Rather, it was just the right attitude that the hapless, clueless, directionless Cubs needed in 1981.

“From top to bottom, the Chicago Cub organization was a disaster area, even worse than I first thought when I took the job.”1 Such was the state of things when Green arrived at Clark and Addison in December 1981, with the Cubs coming off a league-worst finish in the strike-split 1981 season. The team was basically a collection of replacement-level players (please, don’t check the Baseball Reference page), and Green was determined to remake the Cubs in his image. A nearly complete overhaul was necessary, from the players to the front office to the ads to the culture of the whole organization.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. The Great Reboot of 2012-2016 hinged on developing a “Cubs Way,” spearheaded first by the Ricketts family and Theo Epstein, then on Joe Maddon. Green struck out with the Cubs in spring of 1982 with the goal of “building a new tradition,” the first of many Sisyphean attempts to roll the Cubs back to the top of the National League. Among his changes: installing the not-yet-infamous Lee Elia as field manager, trading for a handful of his Phillies regulars (including Ryne Sandberg), and, most notably, beating the drum for night games at Wrigley Field. Green even brought back Fergie Jenkins, after the hurler spent eight years in Texas and Boston.

“The first thing that had to be changed was the work habits. Not only of the ballplayers, but of the entire organization,” Green said when he came on the job.2 The new GM hired, according to his count, 20 new front office staff, in addition to the aforementioned trades. Dividends were not apparent right away: the Cubs won only 73 and 71 games in 1982 and 1983, respectively, and Green had a handful to deal with in the form of the irate Elia. Likewise, he found few sympathizers on the night game front, most notably developing an antagonistic relationship with groups of hardcore fans who wouldn’t dare let their Cubs play under light standards. It wasn’t long before the Tribune hired away Jim Finks from the Chicago Bears to become the new president of the Cubs, a position ostensibly above Green.3

—

“I’ve talked about how you could see the losers’ look, even in the Wrigley Field ushers,” Green observed. “Losing permeates everybody. Losing shrinks people. Losing deteriorates people. Losing destroys people.”

After two years of failure, Green’s Cubs finally matured into a force. The 1984 Cubs won 96 games and lead the NL East, but fell to the Padres in heartbreaking fashion come October. Green summed up the loss in rightfully gruesome and succinct terms: “We had them by the throat and let them get away.” Following the season, Fink stepped down and Green ascended to president of the club.

That offseason, Green participated in the now-traditional Cubs caravan visits throughout the Midwest, an indication of his unusual position as a general manager with a recognizable face. He had re-signed Rick Sutcliffe that winter after trading for him in June, and he publicly opposed new commissioner Peter Ueberroth’s overtures regarding the adverse effects of WGN telecasts on attendance. Green had worked the Cubs’ faithful into a froth, and the 1985 season looked to be just as exciting as the previous campaign.

We know that it never came to be, though, mostly due to myriad pitcher injuries, and Green’s tenure quickly soured. Not only was the on-field product suffering, but the organization was fighting back rumors of a move to the suburbs if the Illinois Supreme Court and other municipal and legal obstacles were not cleared. “The law’s got us, the Legislature’s got us, the City Council’s got us and we’re 0-12. Hey, it’s a horrible year,” Green confessed.4 The club unceremoniously released Larry Bowa, one of Green’s first acquisitions from his former team, in August of 1985, a symbol of the club’s swift downfall. In a bit of overkill (the Cubs were nowhere near October baseball), Major League Baseball wouldn’t even let the Cubs play home playoff games at Wrigley Field, due to the lack of lights.

But, as the pharoah did, Green hardened his heart against those who might help his club succeed. Green became openly antagonistic to Dick Moss, Andre Dawson’s agent, when Moss indicated that he and the Cubs were hoping to come to an agreement to bring the star outfielder to Chicago for the 1987 season. It was in character for the conservative Green, who frequently sided with his bosses when it came to player-management issues. It was that intransigence—an episode in the owners’ collusion against free agents that year—that caused Dawson to hand Green a “blank contract” to play for the club.

Many players left unhappily during Green’s reign, a continuation of his Philadelphia days. His demeanor never softened, and his club never got back to their 1984 peak. Green’s vision met too much resistance, too much pressure from both the traditionalist and the progressive, to succeed in full, and the club quickly fell into the entropy that characterized the four previous decades. After a last-place finish in 1987, despite Dawson’s MVP, the Tribune wanted to install some of their own people in the baseball operations department, and Green balked.

A man of few compromises, Green decided to resign as general manager. Jody Davis and other Cubs had found Green’s moves before and during the season puzzling, and had found them downright sour after the GM blamed the players for their sagging record.5 The old school Green had found himself a man out of step with his team, his city, and his organization.

It’s easy to observe Green’s Cubs tenure more as curiosity than as brilliance, particularly from this vantage point on the other side of the sabermetric looking glass. The Phillies’ chief came to Chicago with a unique plan and an iron will, with little sentimentality to either bar him from pursuing his ends or making friends along the way. He was a precursor to the Cubs’ current regime in many ways—a knack for player evaluation, a fearlessness in the face of long odds—and yet a world apart.

Notes:

[1] “Sports People: A Disaster Area,” New York Times, Dec. 3, 1981.

[2] Dave Anderson, “By Sports of the Times: The Cubs’ New Tradition,” New York Times, March 11, 1982.

[3] Byron Rosen, “Fink Becomes Chief Cub,” Washington Post, Sept. 22, 1983.

[4] “Sports People: Green Feels Unloved,” New York Times, June 26, 1985.

[5] “Cubs’ Davis Blames Green for Fold,” Washington Post, Sept. 29, 1987.

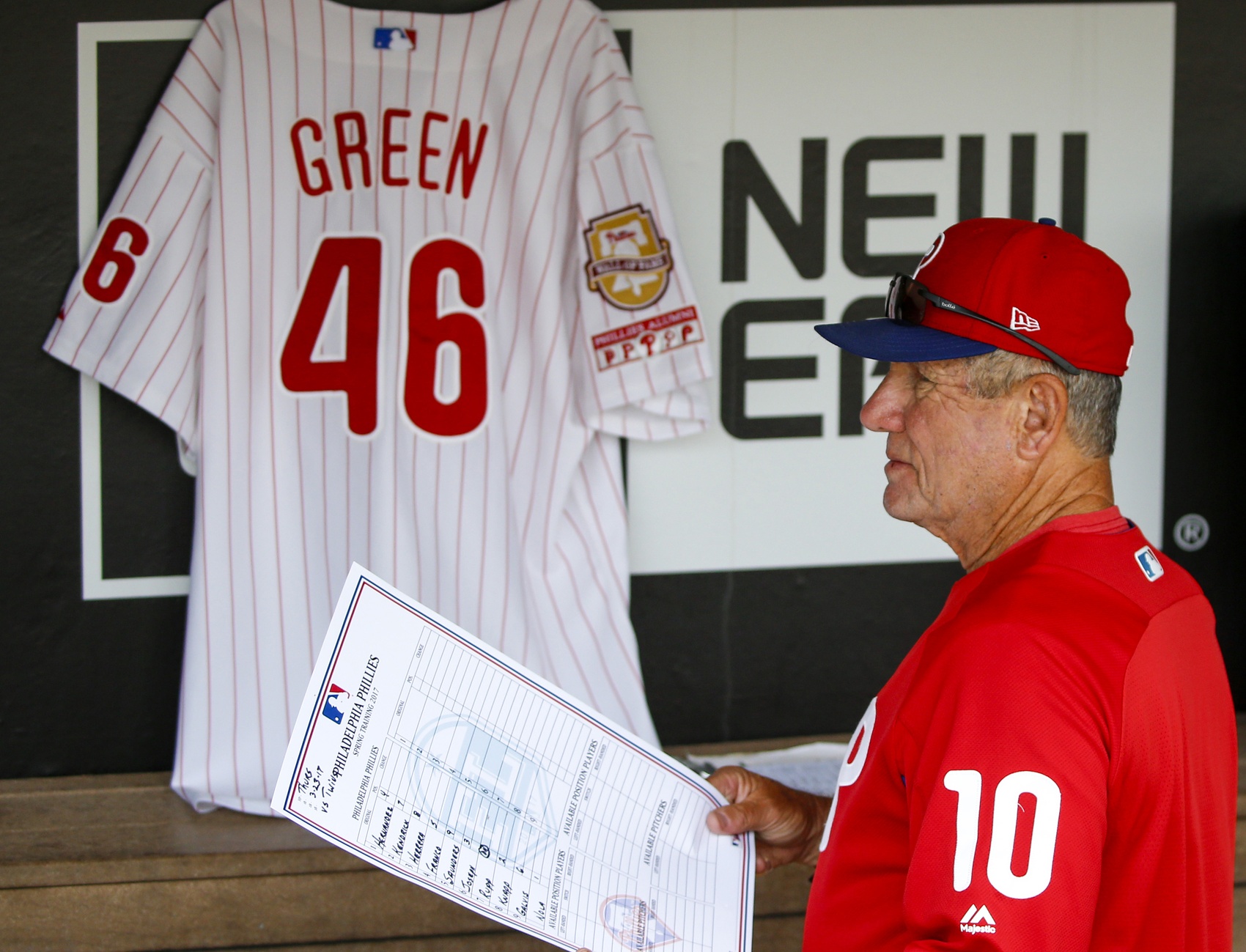

Lead photo courtesy Butch Dill—USA Today Sports

Chuck Tanner never managed the Cubs. Green left because the Trib bosses refused to hire his choice, John Vukovich, as manager. He also built the best farm system in Cubs history before Theo.