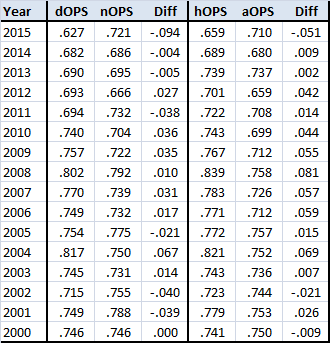

Through Monday, the Cubs are 27-24 at home and 30-23 on the road. I try not to get too carried away over split data, but while this portrays a positive development, there are intriguing undertones. This table shows the difference in OPS for the Cubs since 2000 for home and away games (hOPS and aOPS), as well as day and night (dOPS and nOPS):

The OPS difference between day and night games this year is stark, and believe it or not, has actually decreased over the past week or so—the spread was over 100 points at one point, a figure only achieved by six teams since 2000. It’s fairly uncommon, and in 2015, the Cubs trail only the Angels in the size of the negative spread.

Similarly, the Cubs are hitting worse at home than on the road. There are certain parks where this difference can be easily understood—for example, the Rockies, and to a lesser extent, the Rangers don’t hit as well on the road, because both play in hitter-friendly parks. Likewise, the Padres have historically hit better on the road because for most of its history Petco Park has been a less than hitter-friendly park. The Cubs, however, play in what is generally a hitter-friendly park (note the park factors), making it surprising they have an OPS over 50 points below what they have on the road.

Why might this be? The first answer is the most obvious, and also one that has some element of truth—it’s just noise. In other words, it’s an anomaly that is unlikely to be replicated going forward. I created a Tableau data visualization that shows the day-night data since 1945 and the home-away data since 2000. When looking at the visualization, it’s clear there are few trends—for example, teams rarely perform better or worse than the norm consistently (except for the extreme examples noted earlier), but move back and forth from year to year. There’s a large measure of random chance in baseball, and this is one occasion where it occurs.

The second answer is one I’ve referenced before: the relative youth of the Cubs. By placing a large amount of responsibility on young players like Kris Bryant, Kyle Schwarber, Jorge Soler and Addison Russell, the Cubs are putting their young talent through the cruelest of learning curves, while adding all the pressure that being in a playoff race entails. A home field advantage usually comes about through familiarity with the quirks a home ballpark contains, and can be a competitive advantage in that way, but for the Cubs’ first-year players, Wrigley Field is just another park that needs to be learned. With the frequently changing weather patterns, it can be a difficult to master all the nuances, especially in the first half of a player’s first season when they have so much else going on.

This theory also doesn’t address the day-night differential. Through Monday, the Cubs have played 40 day games, and cumulatively have played the most day games in baseball. Playing day games is difficult—in the summer, it’s hotter and windier, and players need to be at Wrigley Field by around 9 or 10 am, which cuts down on sleep. The ball might be easier to see during the day, but that works to the benefit of both teams.

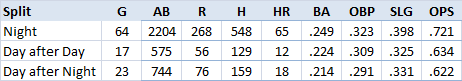

In addition to all those difficulties, the Cubs have played 23 of their 40 day games directly after a night game. This chart furthers stratifies performance by day and night, and also breaks down whether day games follow another day game or a night game:

The day after night games are the toughest games to play, games in which it’s unlikely that the player got home much before midnight but has to be back at the park fairly early the next day. This is hard enough to do in ordinary occupations, let alone one in which physical and mental focus is absolutely required. For a young player, this is a jarring transition, since they played most of their minor league games at night.

As such, it’s not so much a home-away or day-night question, it’s a question of playing a day game after a night game, more than anyone else does. Joe Maddon addressed this earlier this year, and this is where managers and coaches can be invaluable in helping players make an adjustment they’ve never had to make before. In their previous experience, they knew how to perform, but never had to play almost 20 percent of their games on little rest.

Whatever excuse is trotted out to explain these declines (too much partying, lack of training, poor diet, whatever) needs to be balanced against the toll day games take from a player in general, and in particular on day games played after a night game. It’s an equal opportunity detriment to both teams, but veterans (in theory) know how to make these adjustments. This is what the young Cubs are learning on the job.

How unexpected this season has been will be for others to determine, but I believe the Core Four are all ahead of schedule to one extent or another. Injuries and ineffectiveness by Arismendy Alcantara brought Addison Russell to the team earlier than expected, and his stellar play in the field and increasingly productive bat have kept him there. A freak injury to Javier Baez opened the door for Kyle Schwarber in a six-game audition in which he did not disappoint. Throw in a playoff race, and that’s a lot for a young team to shoulder even before you add in the sheer number of day games.

Strategic days off and counseling in how to handle all the rigors of a long, unrelenting season will be invaluable in the development of the young players the Cubs are trotting out. The Cubs have finished the cupcake portion of their schedule; these games against the Pirates and Giants will be very informative and will show how well the Cubs can play against better teams. After this week, they’ll have another 13 games against sub-.500 teams, so it’s not an understatement to say that their performance over the next month will be a primary factor in determining their chances of making the playoffs.

When working with split data, there’s always some underlying story that needs to be teased out. If I were to check other teams, I suspect I’d find similar performance declines in day games after night, but the fact the Cubs play more such games is what is important. It’s not going to change any time soon, given the political complications of the issue, and so it will be in the Cubs’ best interest to learn how to deal with this situation and make the best of it.

Lead photo courtesy of Jason Getz-USA TODAY Sports