The collective sigh of relief when Kris Bryant debuted on April 17th not only signaled the end of Cubs fans’ anxiety, clamoring for their superstar in making—it also signaled an end to the annoyance and frustration of those tired of reading about Bryant’s service time clock, the issue that dominated baseball’s late-winter news cycle. After a torrid spring, Bryant got the call and promptly struck out four times in his debut, before proceeding to put up MVP-caliber numbers in the Cubs’ playoff-bound season.

The sheer volume of columns reporting on Bryant’s service time, replete with quotes from Scott Boras, Tony Clark, and Theo Epstein, along with analysis of MLB’s service time rules, was overwhelming. Awareness about baseball’s labor rules has grown in recent years, with the issues of service time, an international draft, draft slots, and minor-league wages garnering attention from national and local media outlets of all types. The current Collective Bargaining Agreement is set to expire in December of 2016, and negotiations will headline the sport’s news cycle two offseasons from now. Coverage of the negotiations between the MLB Players’ Union and the owners should be better than at any time in the sport’s history: the marriage of good labor reporting and baseball writing is maturing, and it’s no longer taboo to discuss the cognitive dissonance inherent in a sport where we essentially root for ballclub-as-management. If there’s any doubt that this is true, read Michael Baumann’s masterful treatment of the Bryant case, or his attempt at coming to terms with the truly bizarre Matt Harvey innings limit debate.

Three decades ago, robust writing on baseball’s labor environment was the domain of few journalists, ensconced in the nation’s major newspapers. In the mid-1980s, the Cubs found themselves front and center in one of the most important periods in baseball’s labor history, a period that Marvin Miller believed had greater consequences than the Black Sox scandal.

Early Free Agency

The Reserve Clause, an amalgamation of rules stipulated by player contracts and the league’s governing documents that bound players to their club in perpetuity, had come under assault numerous times in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, most notably by St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood in the 1960s. Finally, after nearly a century, the reign of the Reserve Clause ended in 1975, following the decision of arbitrator Peter Seitz in the cases of Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith declaring them free agents.[1] The system thereby established did not resemble the one with which we are familiar today, but it was one of the most radical changes to organized baseball in its history, perhaps second to integration. For the first time in MLB history, players had limited freedom to wield their skills and seniority in pursuit of better salaries.

However, a mere decade after the landmark Messersmith case, free agency had become a farce. In the mid-80s, MLB owners and Commissioner Peter Ueberroth colluded to artificially deflate player salaries by refusing to offer contracts at market value for those reaching their free agent years. Perhaps the most famous instance of this involved Hall of Famer Andre Dawson, the Montreal Expos (for whom he had played his entire career to that point), and Dallas Green’s Chicago Cubs.

The “Blank Contract”

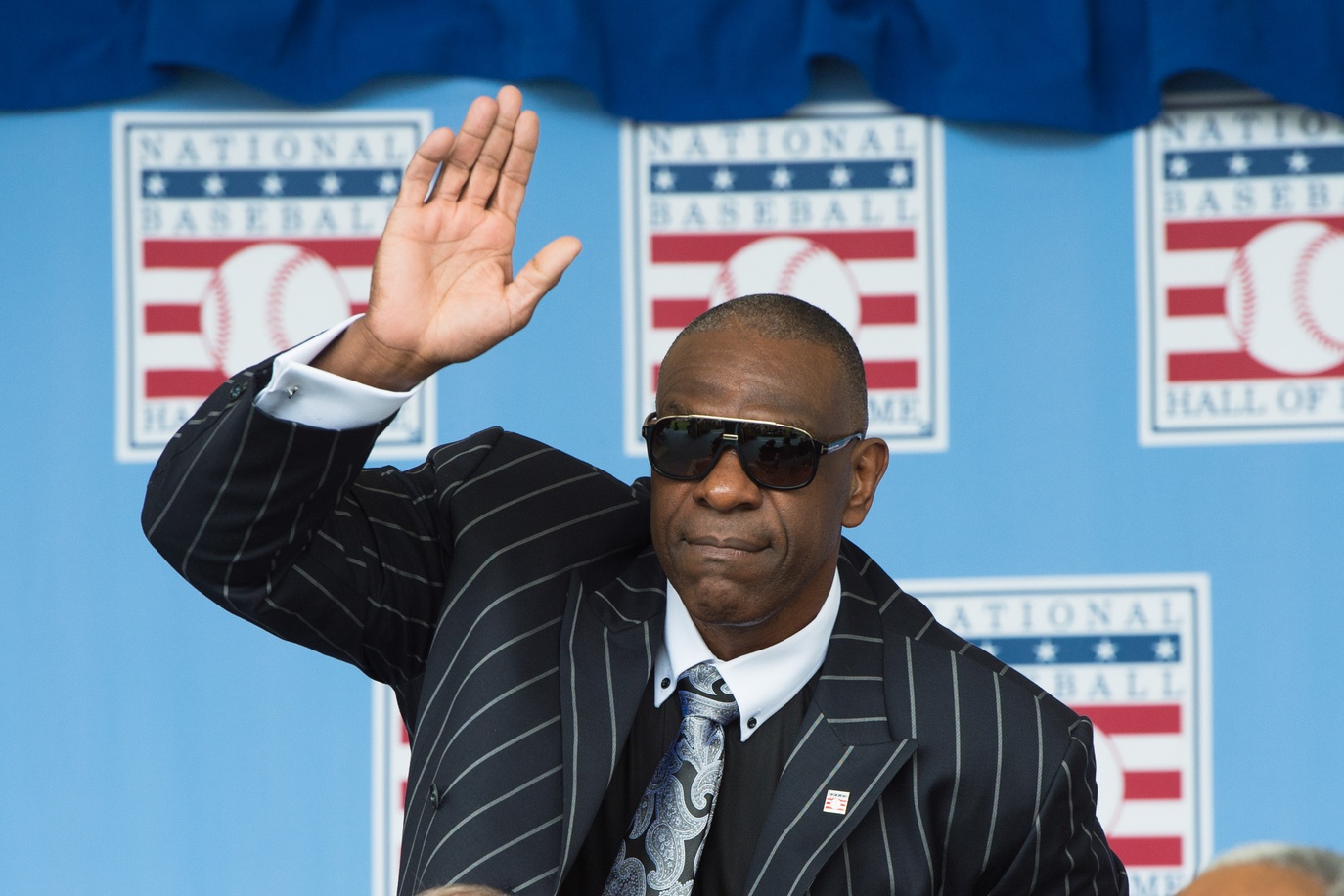

Years of patrolling the artificially turfed right field at le stade olympique de Montrèal had ravaged Dawson’s knees, but The Hawk had accrued a slew of impressive statistics and awards in his 11 seasons there: 1977 NL Rookie of the Year, two second-place NL MVP finishes, six Gold Gloves, 225 home runs, 253 stolen bases, and a .280/.326/.476 line. Going into his age-32 season in 1987, Dawson was indisputably one of the top outfielders in baseball, primed for a big payday.

But the winter of 1987 forced Dawson and other top free agents—among them Tim Raines, Lance Parrish, and Ron Guidry—to stay out in the cold, hoping for contract offers. Dawson reportedly received a two-year, $2 million offer from Montreal, but the right fielder rejected the deal in expectation of more lucrative offers from other clubs.

Per the league’s then-established free-agent system, clubs had until a certain date to re-sign their players heading into free agency. When the deadline passed in mid-January of the 1986-87 offseason, it became clear that Dawson would seek out other clubs, and early reports indicated that he desired to take his talents to Chicago and play for the aging, but talented Cubs.

The Expos weren’t happy with Dawson or his agent, but management offered no comment on the situation. Buck Rodgers, Montreal’s manager, did speak out against Dawson’s agent, Dick Moss, saying, “Dick Moss doesn’t like us. It’s not that we haven’t tried to sign his players. Time after time we’ve made the best offers…. We offered [Dawson] twice as much as he’ll be getting from the Cubs.”[2]

Dawson, Moss, and Dallas Green had been in negotiations publicly since early January. Chicago Tribune columnist Fred Mitchell quoted Green at length:

I’ve told Moss from the beginning, “Tell me what amount of money Andre wants to play for here.” We probably owe him a phone call. I told him our baseball people were very torn about the free-agent situation.[3]

Dawson reasoned publicly regarding his departure from Montreal, stating, “I just asked that they be fair, but one thing they failed to realize is that I have a lot of priorities now—to play on a natural surface, to stay in the National League…. They were asking me to take a cut in pay.”[4] He lamented that the Expos weren’t open to compromise. Most pointedly, he observed, “Baseball is slowly but surely reverting to the way it was 10 or 15 years ago.” It was clear to him that another labor paradigm shift was on the horizon, and soon “collusion” would be the word on the lips of the players’ union.

Talks had stalled by the end of the month, and it was clear that Dawson held no leverage. He wanted to play in Chicago, the Expos couldn’t—and by that point, wouldn’t—take him back, and no other clubs had offered him contracts. Following the Cubs’ trade of third baseman Ron Cey to Oakland, Green remained coy about the club’s newfound financial flexibility, stating, “It may well allow us to make a few phone calls to see where we are.”[5]

In the wake of Dawson’s peculiar situation and those of his fellow free agents, speculation mounted about the reason baseball’s best players were receiving staid contracts, or even pay cuts, from the teams for which they had starred, and receiving none at all from other clubs. Behind closed doors, baseball’s team owners had been shocked by their own financial promiscuity, unable to come to terms with the price of not only the most talented players on the market, but also the average ones. Commissioner Ueberroth pressed the group to discipline themselves in their spending. Ross Newhan of the L.A. Times discussed Angels owners Gene and Jackie Autry’s financial losses, explaining that such conditions “prompted [Gene Autry] to end his spending on free agents.”[6] But the players and the union sensed that something was amiss.

Murray Chass of the New York Times captured both sides’ frustrations in a January 10th column in which he outlined the possibilities (and probabilities) of different situations once the deadline passed for clubs to re-sign their free agents. “Teams could continue to ignore the free agents, despite their proven talent, and make no offers” Chass wrote. “That practice isn’t very likely because it would provide the players’ union with meaty evidence for its ongoing conspiracy case against the owners.”[7]

It quickly became evident that no owners would offer contracts resembling the dollar figures offered by players’ 1986 teams. Not excited about the prospect of being without team for the forthcoming season, Dawson acted boldly: he told Dallas Green that he would sign with the Cubs for any amount that the general manager deemed fair, issuing Green a signed “blank contract.”

It was an unprecedented move, and one only possible under the labor-management dynamics of the day. Once in receipt of Dawson’s unconditional offer, Green released a lengthy statement. “Andre and Dick [Moss] were willing to sacrifice salary and principle in 1987 to play in Wrigley Field for the Cubs. He was willing to bet that his production on the field would better his salary for 1988 and the future.”[8]

Green and the Tribune Company decided that they would give Dawson $500,000 guaranteed, with another $150,000 in incentives. In other words, they gave the All-Star right fielder half of what he would have made in Montreal. Moss explained the rationale behind Dawson’s radical decision: “Our offer was made in the belief that neither the Cubs nor any other team was willing, for whatever reason, to make a bona-fide contract offer to Andre or to any of the star free agents who, until now, remain unsigned.” But those comments were relatively tame compared to others he made around time of the signing.

In the Tribune, Mitchell relayed Moss’s suspicion of the owners. “It’s not only a concert,” Moss said of the owners banding together to deflate salaries, “It’s a symphony and we can all hear the music.”[9] He remained diplomatic when discussing Green, believing that the GM was acting in good faith, but railed against Commissioner Ueberroth as a money-hungry power broker.

To the Courts

Tension between Dawson and the Cubs fell after Dawson’s initial disappointment with his contract terms waned and the season began, but the legal suit the players’ union brought against the owners was only beginning.

The details of the players’ case are somewhat difficult to suss, since their accusations exclusively relied on circumstantial evidence (as one can imagine, the owners weren’t exactly going to admit to wrongdoing), but they were as follows:

- Commissioner Ueberroth, having asked for teams to open up their financial records to each other, pressed teams to discipline themselves in terms of contracts, as noted above. Further, Ueberroth reportedly told owners that their national television contract would be less lucrative when renegotiated in 1989. The union alleged that owners were taking explicit directions from the commissioner not to sign players to lucrative deals.

- Owners publicly expressed their apprehension to agree to long-term free agent contracts.

- The previous offseason (1985-86) resulted in no contracts of greater than three years, and no players received offers from other clubs before the January deadline for re-signing with their 1985 teams.

- Top free agents of the 1986-87 offseason, besides Dawson, remained unsigned until May, including Tim Raines, Ron Guidry, and Bob Boone.

As recourse, the union filed several grievances. Donald Fehr, head of the union, emphatically denied the possibility of a strike. Fehr also signaled that the union would attempt to win damages for all players affected by the owners’ acting in concert.[10] The legal case rested on a provision in the CBA prohibiting players or owners from acting in concert when negotiating contracts.

The legal proceedings dragged throughout the summer, a dark cloud over the baseball season. For his part, Dawson acted anything but distracted. The Cubs’ new right fielder socked 49 home runs, drove in 137 runs, and hit .287/.328/.568 on the year for the last place club, securing the NL MVP over impressive seasons from Tony Gwynn, Jack Clark, Ozzie Smith, Eric Davis, and, coincidentally, Tim Raines. Dawson quickly became a fan favorite for his power, stoic demeanor, and commanding patrol of Wrigley’s notorious sun field.

By September, however, the arbitrator in the union’s grievance cases was set to rule. Arbitrator Tom Roberts found that the owners had colluded after the 1985 season—in which only two players switched teams via free agency—to “destroy” free agency, violating the league’s free market basis as set out in the collective bargaining agreement. In the Baltimore Sun, Tim Kurkjian wrote that the decision “immediately affect[ed] 62 players,” and that Fehr hoped it would be the precedent in future grievances that would be ruled upon soon after. Dawson himself was quoted as saying, “I’m glad the players won, but there’s no doubt in my mind that there was collusion.” [11]

Newhan called the decision a “significant and embarrassing rebuke of Commissioner Peter Ueberroth and the 26 baseball owners. Jack Morris called the owners “crooks.”[12] In early 1988, Roberts awarded 14 players what they called “new look” free agency, or the opportunity to field contract offers without violating their current contracts.

It was an auspicious first decision for the players in a series of cases decided by the arbitrator. Dawson, however, was not affected by this first case. The Cubs tendered him a contract over the winter of 1987-88, but Dawson reportedly sought a four-year deal in the $10 million range. In January of 1988, he filed for salary arbitration.[13] Many believed that Dawson would win a record amount, fresh off his MVP season.

In a surprising turn, the arbitrator ruled against Dawson, who had asked for a $2 million contract for 1988. Instead, finding in favor of the Cubs, Dawson would receive $1.8 million. Before the season began, the Cubs and Dawson actually renegotiated the terms of his contract, drawing up a new two-year deal paying Dawson around $4 million.[14] But, with the second collusion decision still pending, Dawson stood to gain even more if the new arbitrator, George Nicolau, found in favor of the players.

Like clockwork, Nicolau handed down the second collusion decision in September of 1988, once again awarding the players. In his decision, Nicolau even wrote of Dallas Green’s memo to league executives regarding Dawson’s “blank contract.”[15] As a result, Dawson would not be awarded free agency like many other players—his new two-year deal prevented this—but he would be entitled to a portion of the monetary damages awarded to the players, a total of $38 million.

Collusion’s Legacy

Dawson’s contract disputes had ended, but a third collusion case resulted in $280 million total, in the three cases, going from the owners to the players. It took 20 years for the agreement’s terms to be paid out.

Despite the avoidance of a strike, animosity between labor and management was at a high point during these contentious years. Only a few years after the end of collusion, the players union went on strike, resulting in the largest work stoppage in MLB history. Peter Ueberroth wasn’t long for the office of commissioner, resigning the position prior to 1989, immediately following the collusion rulings. His successors, Bart Giamatti and Fay Vincent, were publicly sympathetic to the players—Vincent explicitly called collusion “stealing,” and engaged in niceties that staved off labor strife for a few short seasons. However, when Milwaukee Brewers owner Bud Selig ascended to the commissioner’s office, Donald Fehr and the union saw an owner complicit in collusion now reigned over the game, destroying most chances of reconciliation between labor and management.

Accusations of collusion once again cropped up in 2003, with the union again alleging negotiations in bad faith. The owners agreed to pay $12 million in damages. And just last month, an arbitrator ruled that owners had not colluded against Barry Bonds following his record-breaking 2007 campaign.

Perhaps most significantly, Dawson and his fellow players’ tenacity in the face of collusion altered the free agency system forever. The average player salary in 2015, per the MLBPA, sit at $3,386,212. Players now achieve free-agent status after six seasons of major-league service time, the specific rule germane to the Kris Bryant decision.

Curt Flood, the 1981 and 1994 strikes, and the current peaceful state of labor relations loom large in the collective memory of baseball fans, and rightfully so. But the 1980s collusion cases, spearheaded by Andre Dawson and others, effectively resuscitated free agency after many thought they heard its death rattle.

Lead photo courtesy Gregory Fisher-USA TODAY Sports

[1]http://sabr.org/research/arbitrator-seitz-sets-players-free

[2]Jerome Holtzman, “Raines Will Stay an Expo, After All,” Chicago Tribune, April 1, 1987.

[3]Fred Mitchell, “Green Willing to Talk on Dawson,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 22, 1987.

[4]Mitchell, “Dawson Eager to Sign—but Are Cubs?” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 15, 1987.

[5]Holtzman, “Cey Trade Revives Dawson Talks,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 31, 1987.

[6]Ross Newhan, “Jackie Autry Says Economics, Not Collusion, Causing Solidarity,” Los Angeles Times, Feb. 22, 1987.

[7]Murray Chass, “8 Baseball Free Agents Are Pioneers,” New York Times, Jan. 10, 1987.

[8]Mitchell, “Green: Winning Still up to Dawson’s Teammates,” Chicago Tribune, March 8, 1987.

[9]Mitchell, “Dawson’s Lawyer Sees Hope of Breakthrough,” Chicago Tribune, Feb. 27, 1987.

[10]Newhan, “Baseball Players, Owners Collide on ‘Collusion,’ Los Angeles Times, Jan. 9, 1987; and Newhan, “Collusion? Or a New Coercion?” Los Angeles Times, April 4, 1987.

[11]Tim Kurkjian, “Arbitrator: Clubs Acted in Collusion,” Baltimore Sun, Sep. 22, 1987.

[12]Newhan, “Arbitrator Rules Baseball Owners Guilty of Collusion,” Los Angeles Times, Sep. 22, 1987.

[13]Mitchell, “Dawson, Cubs Heading for Salary Arbitration,” Chicago Tribune, Jan. 5, 1988.

[14]Alan Solomon, “New Deal for Cubs, Dawson,” Chicago Tribune, March 28, 1988.

[15]Mark Hyman, “Owners Guilty of Collusion,” Baltimore Sun, Sep. 1, 1988.

John Helyar has an interesting write up of the mechanics of collusion in the eighties in Lords of the Realm. I have a copy somewhere, I’ll try and dig it up.

I was not aware of this. Great read.