When I wrote of Jake Arrieta, the poet, I wrote of a man opening to us a window unto stories told and retold, a narrative through line from generations past to today. Since, that window has closed slightly. Arrieta has struggled recently, and has looked decidedly human. He’s not bad—far from it. After all, NL manager Terry Collins tapped Jake Arrieta for his first All-Star Game just this week, and he’s a candidate to start the ballgame with Clayton Kershaw on the DL.

Yet, questions linger about Arrieta the Pitcher. He won the Cy Young last season. How? His fielding independent numbers were generally worse that Kershaw’s, and those peripherals have been echoed this season. As Isaac Bennett noted in his superb profile of Kyle Hendricks’s batted ball wizardry, Arrieta leads the ballclub with a .251 BABIP allowed, on a starting staff that has allowed struck balls to fall in for hits at a historically low rate. Last season, Arrieta posted an even better .246 BABIP allowed. The bearded righty has prevented runs though, and at a better rate than anyone else. He’s good at it. He repeats it, over and over, save his recent stretch of mediocrity, and we’ve seemed to reach a collective conclusion that Arrieta is just better than anyone else at inducing softer contact from hitters, even as he strikes out opponents at less than exceptional rates. We’ve answered the primary how, but the secondary questions remain: why is Jake Arrieta so damn good at preventing hits? And, if he’s good at preventing hits, why has he been kind of bad lately?

Unlike Hendricks, Arrieta pairs good velocity with uncanny movement on his pitches to get hitters to not only swing and miss, but also to make weak contact. His slider (a slurvy, cutter-like pitch that dives and darts as manipulated) is his wipeout pitch, and it tops out around 90 miles per hour. It’s not hard to believe that a savvy pitcher with impeccable stuff would be able to reproduce a rate of soft contact above league average, but it’s worth it to know how.

It starts with that slider. Three inches of horizontal break at 90. It’s a hammer, and he’s not afraid to throw it in all counts. Against righties, he uses it between a quarter and a third of the time, even when the batter is ahead. Against lefties, he still uses it liberally, but he peppers in a changeup. The slider gets 17 percent whiffs, and even though Arrieta throws it for a strike more than he does his other pitches, over half of the balls put in play on the pitch result in grounders. Hitters can’t do much with it, even when it’s in the zone. It’s deadly, and it’s the pitch he rode to each of his two no-hitters. Everything else works off the slider.

So, Arrieta has the stuff. To demonstrate how it has translated into success, some illustrative stats from Arrieta’s last three seasons.

| K% | GB% | BABIP | WHIP | oppTAV | DRA | |

| 2014 | 27.2% | 51% | 0.272 | 0.99 | 0.254 | 2.61 |

| 2015 | 27.1% | 58% | 0.246 | 0.86 | 0.256 | 3.02 |

| 2016 | 26.4% | 56% | 0.251 | 1.06 | 0.268 | 3.46 |

Arrieta’s strikeout percentage has never been of the highest echelon—this season he ranks 17th in MLB. His high groundball rate and its attendant weak contact have kept his WHIP, BABIP, and opponents’ True Average down. It’s also important to understand that Arrieta’s BABIP allowed is partially a product of a good defensive unit behind him each day, similar to its affect on Jon Lester’s All-Star 2016, as Jared Wyllys capably analyzed in another piece in this series. But, although Lester has clearly benefited from the defensive efforts of his teammates, Arrieta’s advantages in that regard are murkier. He’s generating a low BABIP, sure, but he did that last year. He’s getting groundballs at the same rate, too. We can determine that “luck” is not the key factor in Arrieta’s opponents’ inability to square him up if we view his quantitative success in that realm as a function of very real qualitative excellence.

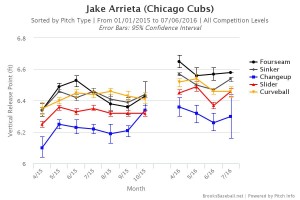

Somehow, though, Arrieta has been appreciably worse for the past month, allowing hits and walks at a high rate, and it appears, sinisterly, that the pitcher himself is the culprit. Arrieta’s release points have faltered from their pristine form, and they seem to be getting worse. Over the weekend, when I recapped Arrieta’s loss to Bartolo Colón in New York, I made note of his high vertical release points in 2016:

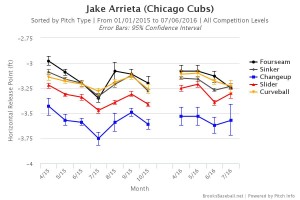

Now, those vertical release points in concert with his horizontal release points from the same period:

Arrieta is throwing more over-the-top, and when he releases the ball it is slightly closer to center than in his sustained period of success. He is a crossfire pitcher—he closes off his body to the hitter, pointing his toe, glove, and shoulder toward third base, before snapping them back toward home and delivering the pitch. As such, he releases the ball closer to third base (farther from zero, on the chart), and compared to a non-crossfire pitcher like Kyle Hendricks, Arrieta releases the ball about nine inches farther from center. This is all to say that Arrieta must maintain those finely tuned mechanics in order to generate the same movement on his pitches, especially his slider.

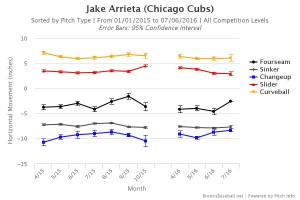

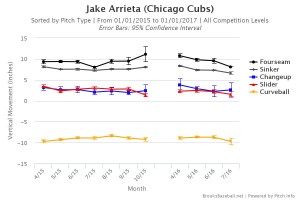

Lately, he hasn’t been able to sync up his body correctly—a point even the FOX broadcast from Saturday noted—and his pitch movement has suffered. A chart of Arrieta’s pitch movement since the beginning of 2015 tells the story:

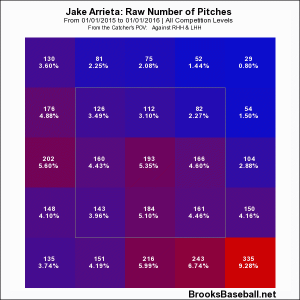

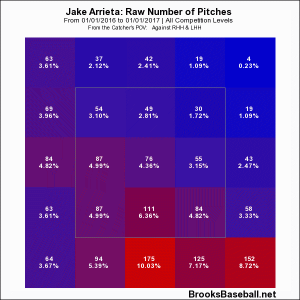

The slider on which he depends has slipped under three inches of horizontal movement for the past month-plus, and both of his fastballs have flattened throughout 2016. Even his seldom-used changeup has crept back toward zero horizontal movement, albeit subtly. Movement is not the only part of Arrieta’s game to suffer, though: his command has been affected as well, as evinced by his 2015 and 2016 zone profiles:

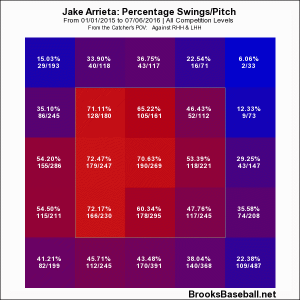

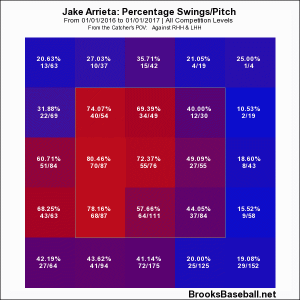

Arrieta is missing toward the middle of the plate in 2016, whereas last year he lived in the pitchers’ happy zone: low and away to righties. As a percentage of pitches, those halving home plate at the knees have doubled! Hitter’s swing rates on pitches in those locations are the most stark differences between Arrieta’s 2015 and 2016.

Hitters are simply not chasing Arrieta’s pitches outside the zone anymore. Slashed in half are swing rates off the outside corner of the plate, while the pitches Arrieta throws in the zone are tantalizing hitters into swinging. Even though Arrieta has continued to get hitters whiff or make weak contact on his remarkable stuff, he’s pitching considerably worse. It’s a troublesome trend, and it’s doubled Arrieta’s walk rate, now at 9.6 percent compared to last season’s 5.5. If we’re willing to conclude, with appropriate caution, that Arrieta’s knack for inducing poor contact is a skill dependent on his nasty slider and his other pitches relative to that slider, then when his slider and other pitches are moving less due to mechanical inconsistencies, and when he is not hitting the outer portions of the strike zone, he will falter.

Luckily, Arrieta is one of the most well conditioned athletes in professional sports, and he works with a pitching coach who has aided in his transformation from Jake Arrieta, flamed out Orioles prospect, into Jake Arrieta, Cy Young winner. Arrieta might be heading to San Diego, but with the All-Star break on the immediate horizon, he still has an opportunity to rest, regroup, and possibly tweak his mechanics to conform to those which propelled him to that shiny hardware last season.

Jake Arrieta can muscle a good pitching performance even when he doesn’t have his best stuff. We saw it in April in Cincinnati, the day he threw his second no-hitter. That’s because he can suppress hits, and he does it with regularity. In his pursuit of pitching excellence, Arrieta crafted both a dynamite slider—a key to that unique skill—and a repeatable delivery that maximizes his stuff’s potential. It’s the latter that he must regain in the second half.

Lead photo courtesy Matt Marton—USA Today Sports.

There is an obviously simple answer here. He stopped with the PEDs once the word got out.