Following the revitalization of its economy from increased manufacturing due to World War I, America entered an era defined by labor crises. Big business sought to push back on the labor unions that had grown in strength in the 1910s, prompting a nationwide labor strike of over four million workers in 1919. Unfortunately, the magnitude of the strike combined with the fear of communism led business owners, politicians, and courts to abolish labor gains like the 48-hour work week and prevent labor unions from achieving their goals. As the epicenter of much of this labor activity, Chicago led the charge against big business and its supporters, one of which happened to be federal judge and MLB commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

Laying the Groundwork for the Boycott

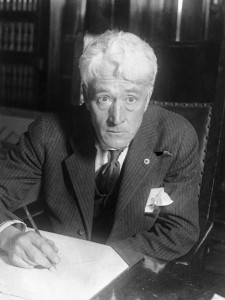

In 1921, the Building Construction Employers’ Association of Chicago attempted a 20 percent wage cut to increase corporate profits and return workers to pre-1917 wages. Naturally, Chicago building unions vociferously protested this action, prompting the Association to implement a lockout affecting roughly 25,000 workers. Eventually, the two sides agreed to enter arbitration and mutually agreed to the case’s arbiter: Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis.

After hearing the case in June, Landis took over three months to make his ruling. Whe n he eventually released his decision, he began by asserting that the “industrial depression [had] resulted in a virtual famine in housing accommodations and brought about the idleness of many thousands of men willing to work.” In an effort to fix this situation, the commissioner of baseball and federal judge ruled in favor of a 12.5 percent wage cut, established a standard overtime rate, created a number of machinery restrictions to limit the number of jobs lost to such machines, and eliminated the prohibition of non-union-made materials.1

n he eventually released his decision, he began by asserting that the “industrial depression [had] resulted in a virtual famine in housing accommodations and brought about the idleness of many thousands of men willing to work.” In an effort to fix this situation, the commissioner of baseball and federal judge ruled in favor of a 12.5 percent wage cut, established a standard overtime rate, created a number of machinery restrictions to limit the number of jobs lost to such machines, and eliminated the prohibition of non-union-made materials.1

These measures, collectively known as the Landis Award, reduced the cost of construction by approximately 30 percent, and in the ensuing months, roughly a half-billion dollars was put into new construction projects in Chicago alone. Newspapers credited Landis with revitalizing the American economy. But many labor unions remained dissatisfied, asserting that the ruling enabled businesses to pay workers less and force them to work longer hours. As the name and face of these regulations, Landis drew much ire from labor unions in Chicago and across the country.

In August of 1921, President Warren G. Harding declared martial law in West Virginia in response to a decade-long miners’ strike that escalated to armed conflict on August 20th. In the presence of 2,500 federal troops, the miners were forced to stand down, but the incident hardened unions across the country who realized they needed to take decisive action. In late 1921, 16 of the country’s largest railway unions began planning the Conference for Progressive Political Action, backed by the Socialist Party. By the time the Conference came together in February of 1922, it represented unions of every labor industry in the country, promising decisive political action to improve the representation of union members in Congress. Invigorated by this movement, union members began to think about other large-scale means of action.

Boycotting in the Midst of Labor Backlash

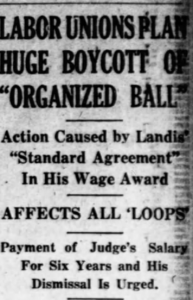

Emmet T. Flood, the Chicago representative of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), led the charge against Landis, asserting that the judge and baseball commissioner had allowed himself to become “a tool of big business in an effort to disrupt building trade unions throughout the country.”2 Prior to the opening of the 1922 MLB season, Flood announced a total union boycott of professional baseball. Speaking to the Associated Press, Flood justified the boycott thusly:

[Landis’s] so-called standard agreement makes the union man as helpless as the professional ballplayer who is bought and sold at the whim of the club owners. It makes the union man work with the nonunion man, under almost any conditions his employer wishes to impose. It will be cheaper in the long run for the magnates of baseball to pay Landis his $50,000 a year for the six years remaining and dismiss him than thus to antagonize organized labor.3

The AP article was re-printed in newspapers large and small across the country. It would be difficult for any worker or baseball fan to be unaware of these events. The stage was set for a standoff of unprecedented proportions.

The official slogan of the boycott, involving one million unionized workers throughout the country, was: “oust Landis, baseball chief, or bust professional baseball.”4 Many unions became so dedicated to the cause that they threatened to fine any member caught attending a professional baseball game. Nonetheless, attendance at games remained almost the same as it had been in 1921, forcing the Chicago Building-Trades Council in mid-May to attempt another, larger boycott. It sent appeals to unions across the country, targeting 2.5 million workers predominantly in the cities home to the nine largest baseball teams: New York, Cincinnati, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, St. Louis, Detroit, and Washington.

The New York World, one of the premiere newspapers in the country known for its support of labor, took the boycott more seriously than most other large papers. Following the announcement of the revamped boycott, the newspaper published its assessment of the events:

If the supreme arbiter of baseball is not ‘regular’ the game itself is under no ban, and a form of punishment for its head which necessitates self-denial on the part of fans imposes a severe strain on human nature. It is altogether, indeed, about the most ambitious punitive campaign in which union labor has ever engaged, and the final outcome will be awaited with interest. For this is not a case of attempting to bring an ordinary industry to terms by retaliatory measures…it is in effect an appeal for a sympathetic strike against a national institution. If organized labor can successfully carry out a boycott against baseball it will have demonstrated its power as never before.5

The newspaper notes the unconventional nature of the strike, but seems to suggest it is doomed to fail because of a lack of direct access to Commissioner Landis. Perhaps because of the improbability of its success, the movement had the power to re-define labor negotiations for decades to come.

Other newspapers stuck more or less to re-publishing a singular article containing updated statements and facts. Occasionally, papers would insert small amounts of editorializing, such as Frank G. Menke of the Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin, who declared the union members’ grievance irrational and an attempt  to harm “innocent baseball club owners” simply because they didn’t like the outcome of the case.56 Otherwise, the largest anti-union newspapers, like the Chicago Tribune and New York Times offered as little coverage as possible, instead focusing on baseball and labor as disparate entities so as to not build any support for the boycott.

to harm “innocent baseball club owners” simply because they didn’t like the outcome of the case.56 Otherwise, the largest anti-union newspapers, like the Chicago Tribune and New York Times offered as little coverage as possible, instead focusing on baseball and labor as disparate entities so as to not build any support for the boycott.

Greatly complicating the boycott was a series anti-labor actions taken up federally and locally in the summer months of 1922. At the same time as the second protest was organized, the US Supreme Court handed down its ruling on Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs et. al., which challenged MLB’s Sherman Antitrust Act exemption. The Court unanimously ruled in favor of the National League, reinforcing the league’s exemption on the grounds that MLB was not engaging in interstate commerce. The case proved a massive victory for Major League Baseball, essentially placing it outside the purview of federal law and therefore giving massive power to team owners to operate their teams as they saw fit. Professional baseball players would continue to have no right to increased salary or free agency.

In June, the Supreme Court handed down its decision on United Mine Workers of America v. Coronado Coal Co., another pro-big business decision. In this one, the Court ruled that labor unions could be held responsible for damages in strikes and were therefore able to be sued by corporations for violating the Sherman Antitrust Act in attempting to prevent inter-state commerce. This ruling coincided with a crackdown in Chicago against unions following the murder of two policemen in May. Over 150 labor leaders, including Emmet T. Flood, were arrested in the ensuing months in an attempt to stamp out opposition to the Landis Award.7

Due to its preoccupation with increasingly dire labor matters, the AFL quickly forgot about the baseball protest shortly after issuing its second plea to union members. Professional baseball suffered no harm from the two months of boycotting, and Commissioner Landis, who never publicly acknowledged the boycott, continued to be praised for the Landis Award by anti-union publications. Landis was further seen as a strong commissioner in all areas, one who would clean up the game following the Black Sox scandal and return it to something worthy of national praise.

What began as an unprecedented labor movement effectively ended without having progressed the labor cause. None of the demands of Flood and the AFL were remotely entertained by any professional baseball executive, and the Landis Award continued to be the standard by which businesses approached labor concerns for much of the 1920s.

Notes:

1 Brick and Clay Record, September 20, 1921, 412-413.

2 Louisville Courier-Journal, April 9, 1922, pg. 54.

3 Louisville Courier-Journal, April 9, 1922, pg. 54.

4 Oakland Tribune, February 9, 1922, pg. 16.

5 Burlington Free press, May 12, 1922, pg. 4.

6 Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin, February 22, 1922, pg. 25.

7 Minneapolis Star Tribune, May 12, 1922, pg. 8.